Marx and Marxism have had the same general goal as anarchists. This is fairly well accepted universally. Recall that in the Era of Romanticism anarchists were entirely composed of anti-capitalist/socialist-oriented anarchists: those who enthusiastically stood against the State, established Religion, and Property. The key difference between these two schools of thought--if you could even call anarchism that--involved the play of governing ideas. Anarchists simply didn't trust any sort of political philosophy or analysis, which also included supposed bourgeoisie extensions of rationalism: science, history, and the use of systematic logic. Marxism made use of these tools because they didn't see that the desired goal of human freedom meant purging ourselves of all the historical benefits that streamed from the State.

Yes, there was a very contentious debate in the IWA--or First International. There's at least two reasons why Marxists dissented on this point: (1) Keep in mind that the reason this sort of union was created was due to the rejection and suppression of European States on key groups of rebellious working-class people. The origins of this movement are rooted in the Rebellion of 1848. (2) Marxists saw the result of this as the State maintaining its power for the time being, and that instead of pushing for some grand--probably unrealistic--revolution (since all such efforts had been an abysmal failure in the-then- very recent past), the alternative idea would be to attempt democratic influence through Parliament. This approach is consistent with Marxism because, as you should recall from the prior implications of our other discussion, Marxism wasn't necessarily for the immediate abolition of the State. The State in Marxism was generally viewed as a simple reality for which it was necessary to include in one's political philosophy and in one's political agendas. This position, however, was simply not relevant to the anarchists who could care less for theory and structured praxis.

However, the State is included in Marxian analysis, but its historical presence isn't seen as something "fixed," but rather it was thought of as a transient phenomenon that would eventually pass from the pages of history.

Again, if one understands Marx's ideas, then his actions--and that of many of his followers' actions--would make perfect sense here. It's simply the dogmatic impulse of his critics to coerce Marx to conform to every 20th century statist corruption.

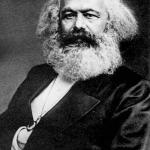

Caption this Meme

Caption this Meme